Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- 1. Introduction

- 2. The Challenge: Why Elementary Flow Mapping Is Required

- 3. High-Level Philosophy Behind Our Mapping Approach

- 4. Mapping Approach

- 4.1 Manual Overrides

- 4.2 Authoritative Mapping Tables

- 4.3 Deterministic and Identifier-Based Automated Matching

- 5. Validation Framework and Findings

- 6. Guidance for Practitioners: When (and When Not) to Use Mapped Impacts

- 7. Overall Conclusion

- Appendix - Useful Flow Mapping References

Executive Summary

EPD program operators are increasingly requiring impact results reported using TRACI 2.2 and EF 3.1, but the core LCI datasets most practitioners rely on do not natively support these methods today. Ecoinvent only implements TRACI 2.1 and has no current plans to add TRACI 2.2, and USLCI / Federal LCA Commons does not provide EF 3.1 at all. This creates a structural gap: verification workflows are asking for indicators that the main datasets cannot directly calculate.

This work closes that gap within CarbonGraph by enabling:

- TRACI 2.2 support for ecoinvent, and

- EF 3.1 support for USLCI / Federal LCA Commons,

using a conservative elementary flow mapping framework that is explicitly designed to be transparent, auditor-friendly, and aligned with community standards.

Approach in Brief

Our mapping approach is built around a strict precedence hierarchy:

Authoritative mapping sources first

- OpenLCA TRACI 2.2 implementation and reference elementary flows for ecoinvent.

- GLAD USLCI → ILCD-EF mapping files and the official EF 3.1 reference packages for USLCI.

Deterministic automated matching next

- Exact name + category + unit group matching.

- CAS-based matching where chemical identifiers are available.

Conservative fallback

- No fuzzy text matching is used for these regulated workflows.

- Any flow that cannot be uniquely and defensibly matched is left unmapped by design.

For TRACI 2.2 on ecoinvent, we mirror all TRACI 2.1 indicators and only replace eutrophication with the regionalized TRACI 2.2 factors from OpenLCA, in line with ecoinvent’s own technical guidance that eutrophication is the only material change. For EF 3.1 on USLCI, we use GLAD’s USLCI → ILCD-EF mappings as the primary bridge, then apply EF 3.1 characterization factors to the mapped flows.

Key Validation Findings

We treat validation as part of the implementation, not an afterthought. The validation program covers:

- Structural coverage (flow-level mapping)

- USLCI → EF 3.1 achieves ~75% structural coverage, consistent with GLAD’s ~89% coverage once USLCI’s expanded flow list in v1.3.0 is accounted for.

- For ecoinvent 3.9.1 and 3.11, 100% of flows with non-zero TRACI 2.1 eutrophication are successfully mapped to TRACI 2.2; global structural alignment is ~90% (3.9.1) and ~66% (3.11), but this does not affect TRACI 2.2 impacts because non-eutrophication indicators are inherited from TRACI 2.1.

- Process-level behavior for TRACI 2.2 (ecoinvent)

- All non-eutrophication indicators are numerically identical between TRACI 2.1 and TRACI 2.2.

- TRACI 2.2 freshwater and marine eutrophication are strongly positively correlated with TRACI 2.1 eutrophication, with differences attributable to the intended regionalized characterization.

- Process-level behavior and outliers for EF 3.1 (USLCI)

- EF 3.1 and TRACI 2.2 climate change impacts are strongly directionally aligned at the process level.

- Absolute differences scale with impact magnitude and remain proportionally small for high-impact processes.

- Relative differences show no correlation with the number of unmatched flows, and inspected outliers are explainable by method differences rather than mapping failures.

Overall, both implementations behave numerically stably, directionally consistently, and in line with their method definitions, with no evidence of structural signal loss introduced by the mapping layer.

Guidance and Limitations

Despite these results, mapped impacts should remain a secondary option. Whenever possible, practitioners should prefer natively supported, dataset-provider LCIA implementations over mapped ones. No mapping framework—no matter how careful—can fully remove semantic and methodological differences between independent LCIA methods and inventories.

However, where program operators require TRACI 2.2 or EF 3.1 and native support does not exist, these mapped implementations provide a defensible, well-documented path to use those methods with ecoinvent and USLCI. The approach is:

- grounded in authoritative community resources (OpenLCA, GLAD, EF packages),

- conservative in what it accepts and what it leaves unmapped, and

- validated structurally and at the process level.

We view this work as one step in an ongoing, community-wide effort to improve interoperability and trust in LCA and EPD practice, and we invite feedback and collaboration to further refine these mappings over time.

1. Introduction

Across the LCA and EPD landscape, there is a growing shift toward more modern and consistent impact assessment methods. EPD Program operators are increasingly requiring that practitioners report indicators using TRACI 2.2 and EF 3.1, reflecting broader alignment with updated scientific models and evolving PCR requirements. These methods capture important changes—particularly in eutrophication modeling and toxicity categories—and are quickly becoming the standard for North American EPD work.

However, the core life cycle inventory (LCI) datasets that most practitioners rely on—ecoinvent and USLCI/Federal LCA Commons—do not yet fully support these updated characterization models today.

- Ecoinvent currently provides only TRACI 2.1 and has stated no plans to add TRACI 2.2.

- USLCI/Federal LCA Commons does not support EF 3.1.

This mismatch creates a structural gap: program operators require impact indicators that the major data sources do not directly support.

The root of the issue is that different LCIA methods define different sets of elementary flows, each with its own naming conventions, category structures, and characterization models. Even when two methods refer to the same chemical substance, they may describe it differently: different names, different categories, different units, or different CAS numbers. As a result, applying TRACI 2.2 or EF 3.1 directly to ecoinvent or USLCI is not possible without reconciling these differences.

To reconcile this gap, the LCA community relies on elementary flow mapping—a process of harmonizing flows across datasets so that they can be correctly recognized and characterized by the target LCIA method. But mapping is inherently a bridge and imperfect. Some flows simply have no equivalents, some differ in subtle but important ways, and some are ambiguous enough that forcing a match would be misleading. The goal is not to eliminate these gaps, but to map conservatively, document transparently, and validate rigorously.

This is where our work comes in. Building on established LCA community mapping approaches and publicly maintained reference mappings, we developed a robust and conservative elementary flow mapping algorithm. Just as importantly, we created a validation framework that allows us to rigorously assess where mapping succeeds, where it falls short, and whether those gaps meaningfully affect impact results. The remainder of this post walks through both our mapping approach and the validation steps we use to ensure the results are transparent, defensible, and aligned with LCA best practice.

The primary motivation for this work is to close that gap by enabling TRACI 2.2 support for ecoinvent and EF 3.1 support for Federal LCA Commons within CarbonGraph. This capability is essential for generating verification-ready EPDs using modern, program-operator-approved methods without requiring practitioners to abandon their existing core LCI datasets. The mapping and validation framework described in this post is the technical foundation that makes this possible.

2. The Challenge: Why Elementary Flow Mapping Is Required

Elementary flow mapping is needed because LCIA methods and LCI datasets speak different “dialects” of the same LCA language. TRACI 2.2 and EF 3.1 define their own elementary flow lists—each representing specific chemicals, elements, and emission pathways exchanged with the environment—while datasets like ecoinvent and USLCI maintain their own independent flow definitions. These differences are not superficial; they reflect decades of separate development by different organizations, each with its own naming systems, category trees, and internal conventions.

Even when two flows refer to the same underlying substance, they may appear differently across datasets:

- different flow names

- different category structures / emission pathways

- different CAS numbers (or missing CAS numbers)

- different unit groups

- different spelling or formatting conventions

For example, a nitrogen oxide emission may appear in one dataset as:

- “Nitrogen oxides, unspecified” → emissions to air → urban air close to ground

while in another it may appear as:

- “NOx” → emissions to air → unspecified

There are differences in category structure, naming format, and sometimes even missing or inconsistent CAS identifiers. To a human practitioner, these clearly represent the same underlying emission. To an LCIA method, however, these are recognized as completely different flows unless they are explicitly mapped.

On top of naming differences, some flows also differ in their characterization models, meaning that even when the substance matches, the emission pathway or environmental compartment may not. For instance, an emission to air versus an emission to water will be assigned entirely different impact factors—or no impact factor at all—depending on the method.

These inconsistencies prevent TRACI 2.2 or EF 3.1 from directly characterizing impacts in ecoinvent or USLCI. A characterization model can only assign impact factors to flows it can identify; if a flow name or category does not match exactly, the result is simply zero impact. In practice, this leads to under-reported impacts and incomplete indicator results—problems that cannot be ignored in verification-driven contexts like EPD development.

On top of all these challenges, there are often hundreds of thousands of elementary flows defined in a given dataset, making 1:1 manual mapping of every flow unrealistic.

This is not a CarbonGraph-specific problem—it is an industry-wide challenge. Every LCA tool, commercial or open-source, must privately maintain its own mapping layer to reconcile flows across datasets. There is no standardized global harmonization, and only partial mappings exist in public sources, such as OpenLCA’s reference flow lists (See “List of References” at the end of this blog post).

Flow mapping therefore plays a crucial role: it connects semantically identical flows across datasets so that updated methods like TRACI 2.2 and EF 3.1 can be used reliably. Our approach focuses on doing this conservatively, ensuring we only map flows that we are confident represent the same underlying substance and emission pathway, and leaving ambiguous cases unmapped by design.

3. High-Level Philosophy Behind Our Mapping Approach

Our flow-mapping philosophy is built around conservatism, transparency, defensibility, and alignment with authoritative community sources. Elementary flow mapping across datasets is inherently imperfect—different LCIA methods define their own flow lists, name chemicals differently, categorize emissions differently, or model environmental compartments in incompatible ways.

Instead of aiming for total coverage or masking these structural inconsistencies, we prioritize correctness over completeness.

Wherever possible, we rely on published, authoritative mapping files already maintained by the LCA community such as:

- OpenLCA provides a comprehensive set of flow definitions that explicitly support all ecoinvent system models.

- The Federal LCA Commons (USLCI) publishes its own mapping files connecting USLCI flows to OpenLCA’s reference flows.

- The GLAD (Global LCA Data Access) initiative maintains a global elementary flow reference framework and supports cross-database mappings, along with a published methodological foundation.

By grounding our work in these external, recognized sources, we minimize the need for CarbonGraph-specific heuristics and avoid introducing unintended bias. Our goal is to layer on top of the mappings the community already treats as canonical—not to invent our own interpretations when authoritative resources already exist.

From there, our algorithm only accepts mappings when the evidence is clear and justifiable. Exact matches, CAS numbers, categories, and unit groups all need to align in a way that leaves no meaningful ambiguity. When the dataset or method does not provide enough information to make a confident match, we intentionally leave the flow unmapped. This prevents silent distortions in impact results and avoids the common industry practice of “forced mapping” designed to inflate coverage percentages.

Because TRACI 2.2 and EF 3.1 are increasingly used in EPD verification workflows, we treat the mapping layer as something that must be audit-friendly. Every automated mapping should be something we can point to and defend—nothing heuristic, nothing hidden, and nothing that would require special justification. And when a mapping is not defendable, it is left unmapped and reported openly.

The final pillar of the philosophy is transparency. By linking to the full set of mapping files used —including exact matches, CAS-based mappings, fuzzy mappings, and all unmapped flows— practitioners, reviewers, and program operators can see exactly where mapping succeeds and where it naturally breaks down.

4. Mapping Approach

Before detailing each step of the mapping algorithm, it’s important to understand the precedence ordering that governs the entire process. The workflow is intentionally designed as a hierarchy, moving from the most authoritative and unambiguous evidence to the least, and stopping as soon as a confident match is found.

The algorithm sequence is:

- Manual Overrides (expert-reviewed, authoritative corrections)

- Authoritative Mapping Tables (community validated, dataset & flow specific)

- Deterministic and Identifier-Based Automated Matching

- Exact Matching (name + category + structural filters)

- CAS Matching (chemical-identity–based matching)

- Fuzzy Text Matching (strictly constrained, last resort)**

- Safe Fallback (flow is left unmapped)

This ordering ensures that we always rely first on trusted community sources and expert judgment, then on deterministic logic, then on chemical identifiers, and only finally on textual similarity. If none of these produce a single clear result, the flow is intentionally left unmapped. This structure allows the mapping layer to remain transparent, conservative, and fully defensible in verification settings.

**Note: Although fuzzy text matching is described as a step in our theoretical matching hierarchy, we did not apply it in the data migration to add TRACI 2.2 support for ecoinvent and EF 3.1 support for USLCI. While fuzzy matching can resolve small naming differences, it is less defensible than the other steps because it relies on linguistic similarity rather than authoritative sources or chemical identifiers. To preserve full transparency and auditability—especially for verification workflows—we intentionally skip this step and treat any flows that reach this stage as unmapped.

Across all automated stages, a single rule governs the workflow:

If a mapping cannot be uniquely and defensibly justified using authoritative sources, deterministic structure, or chemical identity, it is not made.

This principle ensures that coverage is increased only where confidence is high, and that unverifiable matches are excluded by design rather than hidden through forced harmonization.

4.1. Manual Overrides

Manual overrides form the first step of the mapping process and are used sparingly. These overrides exist primarily to handle edge cases that require expert judgment, particularly when authoritative sources are inconsistent, incomplete, or ambiguous.

What kinds of overrides we maintain

Manual overrides are limited to situations where:

- two flows are clearly semantically identical but differ in naming or compartment structure,

- authoritative mapping resources (OpenLCA reference flows, USLCI→OpenLCA mappings, etc.) conflict with each other,

- authoritative sources are silent on a known, commonly accepted equivalence, or

- the flow in question is well understood by practitioners, but automated logic cannot reliably resolve it.

These are not broad interpretations or heuristic guesses—they are corrections grounded in domain knowledge.

When overrides are allowed

Overrides are only introduced when:

- the semantic equivalence between flows is unambiguous,

- external, authoritative resources implicitly or explicitly support the equivalence, or

- failing to override would cause an obviously incorrect omission (e.g., emissions with widely known chemical identities).

When evidence is weaker or ambiguous, we do not add an override—we let the flow remain unmapped instead of injecting a CarbonGraph-specific opinion.

Why overrides are deliberately sparse

Manual overrides are intentionally rare. This prevents CarbonGraph from creating an idiosyncratic or biased mapping layer and keeps the system aligned with recognized community resources. The vast majority of flows should be handled through automated, deterministic rules built on authoritative mapping files—not by custom interventions.

This also ensures that every override is easy to understand, review, and defend.

How manual overrides interact with the algorithm

Manual overrides have highest precedence in the mapping hierarchy. Before any name matching, CAS matching, or fuzzy matching occurs, we check whether the flow has an expert-reviewed override. If so, that mapping is applied immediately and the rest of the algorithm is skipped.

This guarantees that known, authoritative corrections are always honored and prevents automated logic from overriding expert knowledge.

What We Applied in This Data Migration (TRACI 2.2 for ecoinvent & EF 3.1 for USLCI)

For the TRACI 2.2 enablement of ecoinvent and the EF 3.1 enablement of Federal LCA Commons (USLCI), no manual overrides were applied.

4.2 Authoritative Mapping Tables

After applying manual overrides, the next step in the mapping process is to rely on authoritative, community-maintained mapping tables. These resources form the backbone of our approach because they reflect the structural decisions, semantic interpretations, and domain expertise of the organizations responsible for maintaining the underlying datasets and methods.

Why Authoritative Mappings Take Precedence Over Automated Logic

Authoritative mappings take precedence over all automated matching logic because they encode explicit, externally maintained semantic decisions made by dataset stewards and method developers themselves. These decisions reflect intent, scope, and domain interpretation that cannot be reliably reconstructed through deterministic rules alone.

Automated logic—whether based on name matching, structural filters, or chemical identifiers—can only infer equivalence heuristically. Authoritative mappings, by contrast:

- represent upstream domain consensus,

- resolve ambiguities that automated rules cannot distinguish with confidence, and

- preserve formal alignment with verification and regulatory workflows.

For this reason, whenever an authoritative source defines a source-to-target relationship between an inventory flow and a method-level reference flow, that mapping is treated as strictly superior to any automated inference. No attempt is made to “second-guess” or refine these mappings using internal logic.

This precedence structure is critical because:

- misinterpretation at the mapping layer directly propagates into impact results,

- verification workflows require traceability to externally governed sources, and

- the semantic boundary between inventory definitions and method definitions cannot be safely crossed through text similarity or identifier matching alone.

Accordingly, any flow that appears in an authoritative mapping table is accepted immediately and excluded from all downstream automated matching steps.

How Authoritative Mappings Are Applied in the Workflow

Authoritative mappings are applied as direct source-to-target translations between:

- the source elementary flow attached to the existing inventory dataset (ecoinvent or USLCI), and

- the target elementary flow definition used by the LCIA method implementation (TRACI 2.2 or EF 3.1).

Conceptually, the mapping tables define:

- a source side (inventory flow), and

- a target side (method-compatible reference flow).

When a valid source → target relationship exists in an authoritative file, we:

Inherit the characterization behavior of the target flow,

Apply those impact factors to the source flow in place, and

Bypass all subsequent automated matching steps (exact matching, CAS matching, fuzzy logic).

From the perspective of the downstream impact calculation, the source flow is therefore treated as if it were the target reference flow for characterization purposes, while still preserving the original inventory identity for traceability and reporting.

This approach ensures that:

- all characterized impacts are grounded in externally governed method definitions,

- no additional interpretation is introduced after authoritative alignment, and

- all automated logic is reserved strictly for flows not covered by authoritative sources.

What We Applied in This Data Migration — TRACI 2.2 Support for ecoinvent

For enabling TRACI 2.2 support on top of ecoinvent, we relied exclusively on the OpenLCA elementary flow definitions and TRACI 2.2 method implementation as the authoritative target for characterization. We Ingested the official OpenLCA reference elementary flow definitions (v2.7.5) and characterization factors.

OpenLCA maintains a TRACI 2.2 implementation that is explicitly compatible with all supported ecoinvent system models. Accordingly, we used the OpenLCA TRACI 2.2 reference flow set as the method-level source of truth for:

- which elementary flows are characterizable under TRACI 2.2, and

- the corresponding TRACI 2.2 characterization factors.

We also consulted directly with ecoinvent Association regarding native TRACI 2.2 support. They confirmed the following:

“The most recent version implemented in the ecoinvent database is TRACI v2.1. The changes between TRACI v2.1 and TRACI v2.2 are minimal, with the main update being the regionalization of eutrophication characterization factors. The fossil fuel CFs were removed, and zero placeholders were replaced by ‘n/a.’ We have not used the fossil fuel CFs, as the elementary flows in TRACI were different from those in ecoinvent. Therefore, except for eutrophication where CFs are now regionalized, the results should be the same as for TRACI v2.1. At present, there are no confirmed plans or timeline for implementing TRACI 2.2 in the current ecoinvent version line.”

This same technical distinction—that eutrophication is the only materially changed indicator in TRACI 2.2 relative to TRACI 2.1—is also documented by Federal LCA Commons and EPA TRACI.

Based on this confirmation, our implementation strategy was intentionally constrained and conservative:

- For all non-eutrophication indicators, we mirrored the existing TRACI 2.1 characterization factors already used with ecoinvent, with no modification.

- For marine/freshwater eutrophication, we adopted the TRACI 2.2 characterization factors as implemented by OpenLCA,

As a result:

- TRACI 2.2 results are numerically identical to TRACI 2.1 for all indicators except eutrophication by design,

- all eutrophication impacts are grounded in the OpenLCA TRACI 2.2 implementation, and

- no CarbonGraph-specific reinterpretation of TRACI factors was introduced.

This approach allowed us to add full TRACI 2.2 support to ecoinvent inventories in a way that is:

- consistent with ecoinvent’s published LCIA position,

- aligned with the authoritative OpenLCA method implementation, and

- defensible for verification and audit workflows.

What We Applied in This Data Migration — EF 3.1 Support for USLCI

Enabling EF 3.1 impact assessment on top of USLCI / Federal LCA Commons required a fundamentally different strategy than TRACI 2.2 on ecoinvent, because USLCI does not natively align with any EF-compatible elementary flow vocabulary.

Initial Approach and Coverage Limitations

Our initial approach attempted to follow the same architectural pattern used for TRACI 2.2 on ecoinvent: we evaluated whether USLCI flows could be harmonized through OpenLCA reference flow definitions using the Federal LCA Commons → OpenLCA mapping files, and then characterized under EF.

However, this approach revealed a fundamental structural limitation:

- The Federal LCA Commons elementary flow list is substantially larger and more granular than the OpenLCA reference flow list.

- As a result, even in a best-case scenario, mapping USLCI → OpenLCA would only provide coverage on the order of ~25–30% of total USLCI flows.

- This aligns with the coverage limitations reported in the GLAD peer-reviewed mapping benchmarks, where cross-database mapping between USLCI/Federal LCA Commons and ecoinvent achieved only ~28% coverage in comparable configurations.

Because EF 3.1 characterization requires high elementary-flow coverage to avoid systemic under-reporting of impacts, this approach was deemed structurally insufficient for production EF 3.1 support.

Adopted Approach: USLCI → ILCD-EF Mapping via GLAD

To achieve materially higher coverage, we adopted the GLAD elementary flow mapping framework as the authoritative translation layer between USLCI (Federal LCA Commons) and ILCD-EF–compatible elementary flows used by EF 3.1.

In this configuration:

- USLCI remains the source inventory dataset,

- GLAD provides the cross-database mapping logic and reference identifiers, and

- ILCD-EF / EF 3.1 reference flows serve as the target method vocabulary.

As reported in the GLAD peer-reviewed paper, this USLCI → ILCD-EF mapping pathway achieves approximately ~89% elementary-flow coverage, representing a substantial improvement over OpenLCA-mediated harmonization for EF-compatible characterization.

Version Compatibility and Validation

Source side (USLCI / Federal LCA Commons):

- The GLAD mapping files were constructed against USLCI Elementary Flow List v1.0.3.

- Our production dataset uses Federal LCA Commons / USLCI v1.3.0.

- We reviewed the USLCI change documentation and confirmed that the changes between v1.0.3 and v1.3.0 are classified as minor and backward-compatible, with no breaking changes to elementary flow identities.

- On this basis, the GLAD mappings remain valid for our USLCI v1.3.0 source flows.

Target side (ILCD-EF → EF 3.1):

- The GLAD mappings target ILCD-EF v3.0 elementary flows.

- We evaluated the ILCD-EF 3.0 → EF 3.1 change logs and confirmed that:

- EF 3.1 primarily introduces new and updated characterization factors, and

- does not redefine the underlying elementary flow vocabulary in a way that breaks GLAD identifiers.

- As a result, the GLAD target-side mappings remain structurally compatible with EF 3.1 reference flows.

This confirms that the GLAD mapping layer remains a technically valid bridge between:

- USLCI v1.3.0 elementary flows, and

- EF 3.1 reference elementary flows.

How EF 3.1 Characterization Was Applied

With GLAD validated as the translation layer, we implemented EF 3.1 support for USLCI as follows:

Ingested the official EF 3.1 reference elementary flow definitions and characterization factors from the EF 3.1 reference packages.

Applied the GLAD USLCI → ILCD-EF mapping files as the authoritative source-to-target mapping layer.

For each mapped USLCI elementary flow:

- we inherited the EF 3.1 characterization factors from the mapped EF reference flow, and

- applied those factors directly to the originating USLCI flow.

As a fallback we also applied the OpenLCA to Federal LCA commons mapping table for any unmatched flows.

Any unmatched flows were left intentionally uncharacterized under EF 3.1, and surfaced transparently in validation as unmapped flows.

All downstream name-based, CAS-based, or fuzzy matching logic was bypassed for flows resolved through GLAD, consistent with our authoritative-first philosophy.

Summary of the Authoritative Mapping Layer

Taken together, these authoritative mapping layers establish the first and most decisive translation step in our overall mapping hierarchy. Wherever an externally governed source defines a valid relationship between an inventory flow and a method-level reference flow, that relationship is accepted as final and all downstream automated logic is deliberately bypassed.

This ensures that the resulting TRACI 2.2 and EF 3.1 characterizations are grounded in community-maintained standards, peer-reviewed harmonization frameworks, and official method reference packages, rather than internal inference. By constraining this step strictly to externally validated sources, we preserve semantic integrity, maximize auditability, and ensure that all subsequent automated matching operates only on the residual set of flows not already resolved by authoritative consensus.

4.3. Deterministic and Identifier-Based Automated Matching

After manual overrides and authoritative mapping tables have been applied, all remaining unresolved flows enter a unified automated matching stage. This stage applies a sequence of increasingly permissive—but still fully deterministic and chemically grounded—matching rules. Each step attempts to resolve semantic equivalence with high confidence, and the process halts immediately once a single, unambiguous match is identified. If no such match can be defensibly justified, the flow is intentionally left unmapped.

This automated layer is designed to maximize defensible coverage without introducing heuristic or interpretive bias.

Deterministic Name and Structure Matching

The first automated step attempts to resolve flows through exact, deterministic alignment of structural attributes. Candidate matches are identified by:

- Exact flow name match (case-insensitive), followed by simultaneous application of:

- Environmental category / compartment (after category harmonization),

- CAS number (when present), and

- Unit group (mass, energy, volume, etc.).

If this strict interpretation produces exactly one valid candidate, the mapping is accepted immediately.

Because CAS numbers are not always present or consistently populated across datasets, the algorithm then applies a controlled relaxation:

- The CAS requirement is relaxed, but

- Category and unit group constraints are still enforced strictly.

If this relaxed pass yields exactly one candidate, the mapping is accepted. If ambiguity remains or no candidate exists, the flow proceeds to chemical-identifier matching.

This two-tier deterministic structure ensures that the algorithm always prefers the highest-confidence structural interpretation first, while still accommodating known metadata gaps in real-world LCI datasets.

Chemical Identifier (CAS-Based) Matching

When deterministic name-and-structure matching cannot produce a unique result, the algorithm attempts CAS-based matching. CAS numbers provide a globally standardized chemical identifier that is independent of naming conventions, spelling, or formatting.

The CAS matching process:

Identifies all reference flows that share the same CAS number as the source flow.

Applies category and unit-group filters to ensure environmental and quantitative consistency.

If a single candidate remains, the mapping is accepted.

CAS matching is particularly valuable for resolving:

- synonym differences,

- naming format variations, and

- capitalization or punctuation differences.

However, CAS matching is not applicable to:

- particulate matter size fractions (e.g., PM2.5, PM10),

- aggregated biological or multi-constituent flows,

- ionized species without stable CAS identity, and

- many resource withdrawal flows.

Where CAS matching cannot be applied or remains ambiguous, the algorithm does not force a resolution and instead advances to the final stages.

Fuzzy Text Matching

In theory, the final automated option would be fuzzy text matching, which attempts to match flows based on string similarity alone. While this can capture minor spelling, formatting, or abbreviation differences, it lacks:

- chemical guarantees (unlike CAS),

- authoritative grounding (unlike OpenLCA, GLAD, or EF reference mappings), and

- strong audit defensibility.

For this reason, fuzzy text matching is intentionally disabled in this data migration. We describe it here only for transparency. Any flow that would require fuzzy logic to resolve is instead treated as unresolved and passed to conservative fallback.

This design choice ensures that:

- no linguistically inferred matches influence regulated results, and

- all accepted mappings remain chemically and structurally defensible.

Safe Fallback: Intentionally Unmapped Flows

If a flow cannot be matched through:

- authoritative mappings,

- deterministic name-and-structure alignment, or

- CAS-based chemical identity,

it reaches the final step: safe fallback.

At this stage:

- the flow is left unmapped by design,

- no TRACI 2.2 or EF 3.1 impact factors are applied, and

- no surrogate or approximate characterization is introduced.

This ensures that:

- no incorrect impacts are assigned,

- no ambiguous decisions are hidden through forced resolution, and

- the integrity of regulated results is preserved.

Unmapped flows are tracked internally as part of the validation process and reviewed in aggregate to understand coverage and potential method limitations. In most cases, these unmapped flows correspond to exchanges that the target methods do not characterize in the first place, meaning their exclusion does not materially affect impact completeness.

5. Validation Framework and Findings

With the authoritative and automated mapping layers established, the remaining question is not whether flows can be mapped, but whether the resulting impact calculations behave as expected in practice. Because elementary flow mapping is inherently imperfect—and because TRACI 2.2 and EF 3.1 are increasingly used in verification-driven contexts—we treat validation as a core component of the implementation rather than an after-the-fact check.

The goal of validation is not to “prove” correctness in an absolute sense, but to test for internal consistency, confirm expected behaviors, identify material outliers, and ensure that the application of mapped characterization factors remains conservative and defensible.

5.1. Validation Goals and Practical Constraints

The validation work for this effort was designed around four primary goals:

- Confirm that structural flow mapping behaves as expected, particularly in terms of matched versus unmapped flow coverage.

- Verify that TRACI 2.2 behaves identically to TRACI 2.1 for all indicators except eutrophication, as expected from the method definition.

- Evaluate whether EF 3.1 impacts applied to USLCI via GLAD behave consistently at the process level, including identifying any obvious outliers.

- Assess whether unmapped flows materially affect total impacts for the indicators of interest.

At the same time, there are important practical constraints on what validation can and cannot demonstrate. There is no direct, ground-truth way to independently verify that any LCIA method’s impact values are “correct” in an absolute sense. Differences observed between TRACI 2.1, TRACI 2.2, and EF 3.1 for the same process may arise from:

- legitimate differences in characterization factors,

- structural differences between methods,

- or residual imperfections in flow mapping.

As a result, the validation focuses on expected directional behavior, internal consistency, relative agreement, and outlier detection, rather than absolute numerical truth.

5.2. Structural Validation: Flow-Level Mapping Coverage

Structural validation examines the percentage of elementary flows that are successfully mapped versus left unmapped, independent of impact magnitudes. This provides a baseline understanding of how much of each dataset’s flow vocabulary is structurally aligned with the target method, and—more importantly—whether impact-relevant flows are preserved under the new TRACI 2.2 and EF 3.1 implementations.

5.2.1. USLCI → EF 3.1 Structural Coverage

For USLCI mapped to EF 3.1 via the GLAD mapping framework, the observed structural mapping coverage in our implementation is approximately 75% of elementary flows.

This coverage level must be interpreted in the context of USLCI version growth:

- The GLAD mappings were developed against USLCI Elementary Flow List v1.0.3, which contained approximately 278,000 flow definitions.

- Our implementation uses Federal LCA Commons Elementary Flow List v1.3.0, which contains on the order of 330,000 elementary flows—an increase of more than 50,000 additional flow definitions.

- These additional flows expand the denominator substantially beyond what existed at the time GLAD coverage was originally reported.

When the originally reported ~89% GLAD coverage is adjusted for this expanded flow vocabulary, the expected effective coverage drops to approximately ~72%, which is nearly identical to the ~75% observed in practice.

Importantly, the achieved ~75% coverage reflects both:

- direct application of the GLAD USLCI → ILCD-EF mappings, and

- additional matching of newer USLCI flows through deterministic exact matching and CAS-based matching applied on top of the GLAD layer.

From an impact perspective, this level of structural coverage is sufficient to support EF 3.1 characterization of dominant contributor flows, particularly for climate change, which was the primary motivation for enabling EF 3.1 on USLCI.

Conclusion (USLCI → EF 3.1): The observed structural coverage is fully consistent with expectations given USLCI vocabulary expansion, and additional deterministic + CAS matching successfully recovers a portion of newly introduced flows beyond the original GLAD mapping set.

5.2.2. ecoinvent 3.9.1 and 3.11 → TRACI 2.2 Structural Coverage

Structural validation for ecoinvent 3.9.1 and ecoinvent 3.11 was evaluated using two complementary lenses:

Eutrophication-relevant coverage (method-critical subset)

Global elementary-flow coverage relative to OpenLCA reference flows

Eutrophication-Relevant Flow Coverage

Across both ecoinvent 3.9.1 and 3.11:

- 100% of the elementary flows that carried non-zero eutrophication impacts under TRACI 2.1 were successfully mapped to OpenLCA reference flows that carry TRACI 2.2 eutrophication characterization factors.

- This confirms that no eutrophication signal was lost in the transition from TRACI 2.1 to TRACI 2.2.

- All TRACI 2.2 eutrophication factors were therefore applied to exactly the same impact-relevant flow population that previously drove TRACI 2.1 eutrophication results.

This is the controlling structural metric for TRACI 2.2, since eutrophication is the only category that changes between TRACI 2.1 and TRACI 2.2.

Global Structural Coverage (ecoinvent → OpenLCA)

When considering all elementary flows, regardless of whether they are characterized under TRACI:

- The global structural match rate is approximately 90% for ecoinvent 3.9.1.

- The corresponding global structural match rate is approximately 66% for ecoinvent 3.11.

The reduction in global structural alignment in ecoinvent 3.11 reflects dataset evolution and expansion, with the introduction of additional or more specialized flow definitions that fall outside the strict OpenLCA reference alignment.

Category-Level Impact-Relevant Coverage

When restricting the analysis specifically to flows that originally carried non-zero TRACI 2.1 impacts, coverage is substantially higher and highly consistent across both ecoinvent versions:

- Climate change, acidification potential, particulate matter, and several other major midpoint categories exhibit effectively perfect structural mapping (≈100%).

- The only categories with less-than-perfect alignment are those with high chemical granularity and complex speciation, including:

- Ecotoxicity (~75%),

- Human toxicity (~80%),

- Photochemical ozone formation (~96%).

These residual gaps are stable across both ecoinvent 3.9.1 and 3.11 and reflect:

- inherent complexity of those flow groups,

- CAS and naming inconsistencies across datasets, and

- deliberate conservative exclusion by structural and identifier filters.

Because these categories were not modified under TRACI 2.2, these structural gaps do not affect any TRACI 2.2-specific behavior.

Conclusion (ecoinvent → TRACI 2.2): While global structural flow alignment differs between ecoinvent 3.9.1 and 3.11, all impact-relevant eutrophication flows are fully preserved, and all other indicators remain inherited from the native TRACI 2.1 implementation. As a result, structural vocabulary differences between ecoinvent versions do not affect TRACI 2.2 impact integrity.

5.2.3. Overall Structural Coverage Conclusion

Across both USLCI and ecoinvent, we did not expect to achieve 100% global structural flow coverage, nor is that necessary for defensible LCIA application. Instead, the design objective was to:

- guarantee complete coverage of impact-relevant flow populations where methods differ,

- avoid over-reliance on fragile global vocabulary alignment, and

- preserve numerical continuity with native, provider-supplied LCIA behavior wherever possible.

The combined strategy successfully avoids the major pitfalls of cross-database flow harmonization while maintaining high practical coverage, numerical stability, and audit-ready defensibility.

5.3. Process-Level Validation for TRACI 2.2 on ecoinvent

Process-level validation for TRACI 2.2 on ecoinvent was designed to confirm two things:

That all non-eutrophication indicators remain numerically identical to TRACI 2.1, as required by the method definition and by the inheritance-based implementation strategy.

That eutrophication impacts reflect only the intended methodological differences between TRACI 2.1 and TRACI 2.2, without introducing distortions from flow mapping.

Validation was carried out for both ecoinvent 3.9 and ecoinvent 3.11 using direct process-level impact comparisons.

5.3.1. Non-Eutrophication Indicators

For all non-eutrophication indicators, we performed a direct before-and-after comparison of process-level impacts under:

- TRACI 2.1 (baseline), and

- TRACI 2.2 (new implementation).

All non-eutrophication indicators are numerically identical before and after the transition to TRACI 2.2.

- Differences are zero within machine precision.

- No systematic bias, scaling error, or structural drift is observed.

This confirms that the inheritance-based implementation strategy for all non-eutrophication indicators behaved exactly as designed, and that introducing TRACI 2.2 did not alter any indicators outside eutrophication.

5.3.2. Eutrophication-Specific Behavior

Eutrophication is the only impact category that changes between TRACI 2.1 and TRACI 2.2 due to the introduction of separate freshwater and marine characterization models. As a result, eutrophication received focused, category-specific validation.

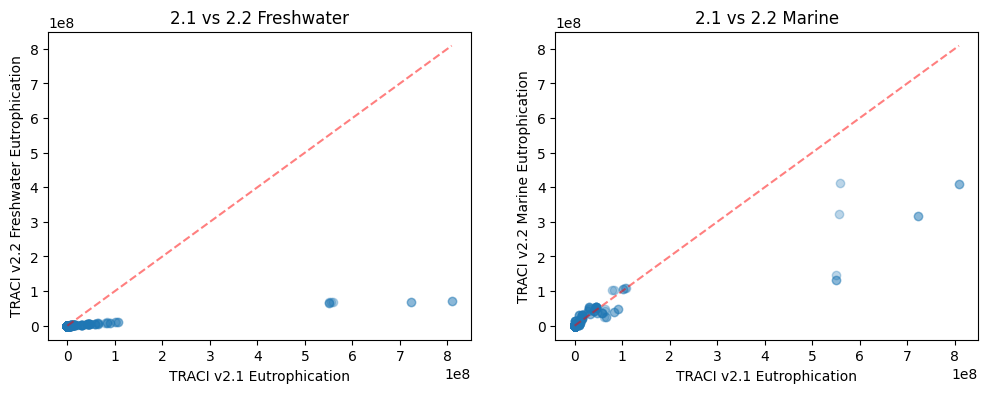

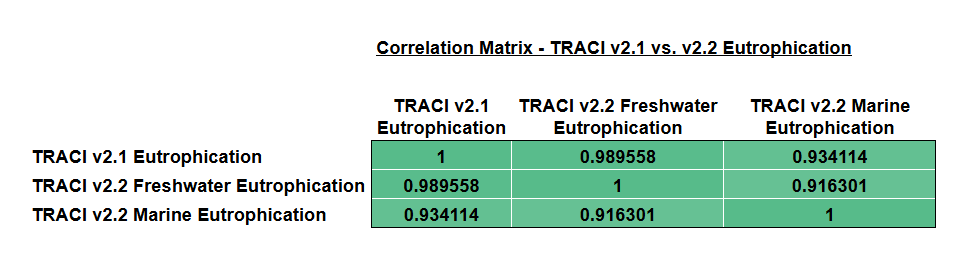

To assess directional correctness and internal consistency, we generated process-level scatterplots comparing TRACI 2.1 eutrophication impacts to TRACI 2.2 freshwater and marine eutrophication impacts.

Figure: Process-level comparison of TRACI 2.1 eutrophication and TRACI 2.2 Freshwater Eutrophication impacts.

Figure: Correlation matrix of process-level eutrophication impacts across TRACI 2.1 and TRACI 2.2 freshwater and marine categories.

These plots demonstrate that:

- TRACI 2.1 eutrophication and TRACI 2.2 freshwater eutrophication are strongly positively correlated.

- TRACI 2.1 eutrophication and TRACI 2.2 marine eutrophication are also strongly positively correlated.

- Across processes, TRACI 2.2 marine eutrophication generally exhibits larger magnitudes than freshwater eutrophication, consistent with the structure of the updated method.

Because 100% of eutrophication-relevant flows were successfully mapped, any differences between TRACI 2.1 and TRACI 2.2 eutrophication results arise solely from differences in characterization models, not from loss of contributing flows.

These results indicate that:

- Eutrophication impacts remain directionally consistent across versions,

- The separation into freshwater and marine sub-categories behaves as expected, and

- No anomalous distortions were introduced by the mapping layer.

5.3.3. Summary of TRACI 2.2 Process-Level Validation

In summary:

- All non-eutrophication indicators are preserved exactly from TRACI 2.1, as expected by design.

- TRACI 2.2 freshwater and marine eutrophication impacts are strongly and positively correlated with TRACI 2.1 eutrophication, demonstrating directional correctness.

- All eutrophication-relevant flows are fully represented, so observed differences reflect methodological updates only, not mapping artifacts.

Together, these results confirm that the TRACI 2.2 implementation on ecoinvent is numerically stable, directionally correct, and faithful to the intended method updates, making it suitable for verification-driven applications.

5.4. Process-Level Outlier Analysis for EF 3.1 on USLCI

Unlike the TRACI 2.1 → TRACI 2.2 transition on ecoinvent, USLCI does not natively provide EF 3.1 impacts, and there is therefore no direct numerical baseline for one-to-one validation. EF 3.1 represents a fundamentally different characterization framework than TRACI 2.2, particularly for climate change, toxicity, and normalization assumptions. As a result, validation for EF 3.1 on USLCI must focus on relative behavior, proportional consistency, and outlier detection, rather than exact agreement.

The goal of this section is to evaluate whether the GLAD-based EF 3.1 implementation on USLCI:

- behaves in a numerically stable and directionally consistent manner at the process level,

- preserves the expected ordering and scaling of impacts relative to established TRACI 2.2 results, and

- does not exhibit systematic distortions or mapping-driven anomalies.

To assess this, we compare EF 3.1 and TRACI 2.2 impacts for the same USLCI processes using:

absolute difference vs. impact magnitude analysis,

relative difference vs. unmatched-flow counts, and

targeted inspection of climate change outliers.

5.4.1. Absolute Difference vs. Impact Magnitude (Global Behavior)

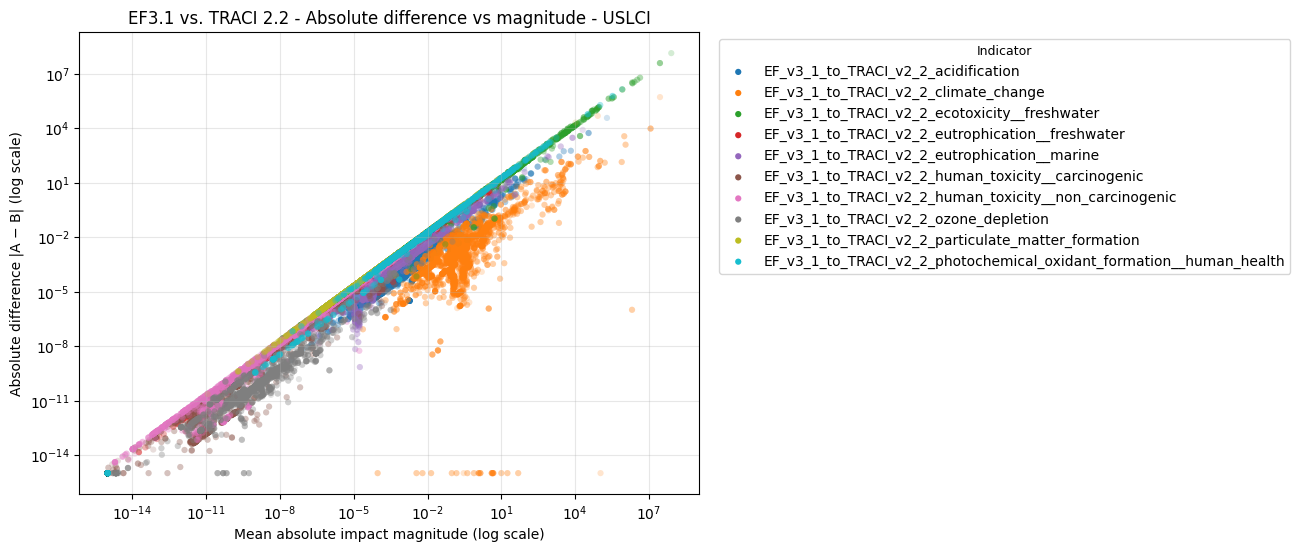

To evaluate proportional consistency between EF 3.1 and TRACI 2.2 process-level impacts, we plotted the mean absolute impact magnitude of each process against the absolute difference between EF 3.1 and TRACI 2.2 impacts, on log–log scales.

Figure: Absolute difference versus mean absolute impact magnitude for EF 3.1 and TRACI 2.2 process-level impacts (log–log scale).

This comparison reveals a clear and expected scale-dependent relationship:

- Absolute differences increase proportionally with absolute impact magnitude, producing a strong diagonal trend.

- The majority of points fall well below the 1:1 diagonal, indicating that for most processes the absolute difference is materially smaller than the impact magnitude itself.

- This behavior is especially strong for high-magnitude indicators such as climate change, where the absolute deviation is typically several orders of magnitude smaller than the underlying impact.

This pattern indicates that EF 3.1 and TRACI 2.2 impacts are directionally aligned across the full impact range, and that observed differences scale naturally with system magnitude rather than appearing as random or mapping-driven distortion.

5.4.2. Relative Difference vs. Number of Unmatched Flows

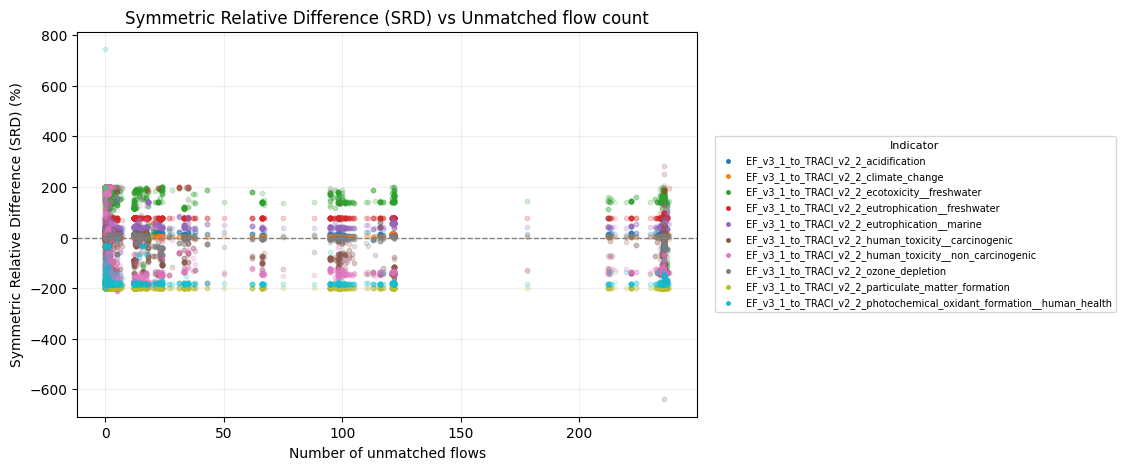

To test whether incomplete structural flow mapping was contributing to large numerical deviations, we compared the symmetric relative difference (SRD) between EF 3.1 and TRACI 2.2 results against the number of unmatched flows per process.

Figure: Symmetric relative difference (SRD) versus number of unmatched elementary flows for EF 3.1 and TRACI 2.2 process-level impacts.

This analysis shows:

- No systematic correlation between SRD and the number of unmatched flows.

- Processes with very few unmatched flows span the same SRD range as those with many unmatched flows.

- Large relative differences occur across the full range of unmatched-flow counts, rather than clustering at high-unmatched values.

This is an important validation result: it demonstrates that relative numerical differences between EF 3.1 and TRACI 2.2 are not structurally driven by unmatched elementary flows. Instead, observed differences reflect method-level characterization behavior, not loss of inventory signal.

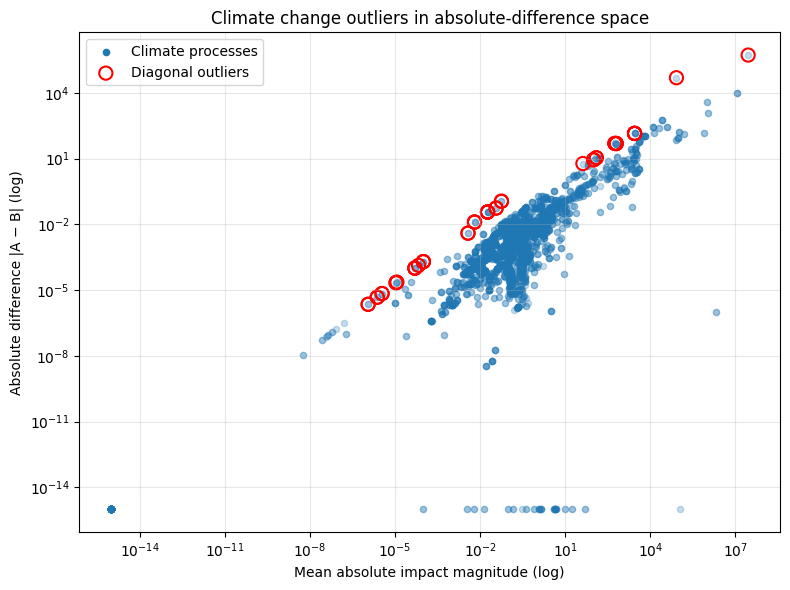

5.4.3. Targeted Review of Climate Change Outliers

We performed a focused review of the climate change processes that fall above the main diagonal in the absolute-difference vs. magnitude space—i.e., those with disproportionately large EF 3.1 vs. TRACI 2.2 differences relative to their scale.

Figure: Targeted review of climate change outliers in absolute-difference versus impact-magnitude space for EF 3.1 and TRACI 2.2.

Manual inspection of these highlighted outliers shows that they fall into two primary classes:

Processes with very small absolute TRACI 2.2 impacts, where even modest absolute EF 3.1 differences produce large relative deviations.

Processes whose differences could be explainable by methodological differences between EF 3.1 and TRACI 2.2 climate characterization:

Critically, none of the reviewed outliers exhibited:

- loss of dominant greenhouse gas contributors,

- evidence of systematic flow loss due to mapping gaps, or

- structural inconsistencies traceable to the GLAD mapping layer.

5.4.4. Interpretation and Validation Conclusion

Taken together, the three analyses support a consistent and defensible interpretation:

- EF 3.1 and TRACI 2.2 climate change impacts are strongly directionally aligned at the process level.

- Absolute differences scale naturally with impact magnitude and remain proportionally small for high-magnitude processes.

- Relative differences are not correlated with unmatched flow counts, indicating that structural mapping gaps are not driving numerical divergence.Apparent outliers are explainable either by small-magnitude denominator effects or legitimate method-level characterization differences.

These results provide strong evidence that the GLAD-based EF 3.1 implementation on USLCI behaves numerically stably at the process level, and that observed deviations from TRACI 2.2 reflect methodological differences, not mapping artifacts.

5.5. Overall Validation Summary

Taken together, the structural and process-level validation results demonstrate that both implementations—TRACI 2.2 on ecoinvent and EF 3.1 on USLCI—behave in a numerically stable, directionally consistent, and methodologically defensible manner.

Across all validation layers, we confirm that:

- Structural flow mapping behaves as expected for both datasets, with full preservation of impact-relevant flows for TRACI 2.2 on ecoinvent and coverage levels for EF 3.1 on USLCI that are consistent with GLAD-reported performance once dataset growth is accounted for.

- TRACI 2.2 is implemented exactly as designed:

- All non-eutrophication indicators are numerically identical to TRACI 2.1.

- Eutrophication behavior changes only in the intended manner through freshwater and marine regionalization.

- EF 3.1 on USLCI exhibits strong directional agreement with TRACI 2.2 at the process level, particularly for climate change:

- Absolute differences scale proportionally with impact magnitude.

- Relative differences show no correlation with unmatched flow counts.

- Identified outliers are explainable by known method-level modeling differences, not by mapping failures.

Importantly, we reiterate a fundamental limitation of any cross-method validation exercise: it is not possible to directly isolate whether a numerical difference arises from flow mapping versus from underlying characterization model differences. For this reason, the validation framework intentionally focuses on:

- preservation of dominant contributors,

- proportional stability across magnitude ranges, and

- detection of systematic anomalies rather than pointwise numerical equality.

Within those constraints, the combined evidence indicates that both implementations behave consistently with their respective LCIA method definitions and are suitable for verification-driven use cases, with no signs of structural signal loss or uncontrolled numerical distortion introduced by the mapping layer.

6. Guidance for Practitioners: When (and When Not) to Use Mapped Impacts

Elementary flow mapping is, by its nature, an approximation layered on top of the original inventory and characterization frameworks. While we have taken a deliberately conservative, transparent, and defensible approach to implementing TRACI 2.2 on ecoinvent and EF 3.1 on USLCI, mapped impacts should always be viewed as a secondary option rather than a primary source of truth.

Whenever possible, practitioners should prioritize impact results that are natively provided and validated by the original dataset publishers and method developers. These native implementations benefit from:

- direct internal consistency between inventory and characterization,

- full control over method assumptions, and

- validation within the same institutional framework that produced the data.

Mapped impacts, by contrast, necessarily introduce an additional layer of interpretation—no matter how conservative the approach. Even when structural coverage is high and process-level behavior is well-validated, it is not possible to fully disentangle the effects of flow mapping from the inherent differences between LCIA characterization models.

That said, we recognize that program operator requirements increasingly mandate TRACI 2.2 and EF 3.1, even when the underlying datasets do not natively support them. In these cases, mapped impacts become a practical necessity rather than a theoretical preference. Our goal in publishing this work is to ensure that:

- the mapping logic is explicit and reviewable,

- validation behavior is quantitatively demonstrated, and

- users understand both the strengths and limitations of the resulting indicators.

We encourage practitioners, verifiers, and method developers to:

- use these mapped impacts only when native alternatives are unavailable,

- interpret results with appropriate methodological context, and

- engage with the broader LCA community to continue improving public harmonization resources.

We view this work as part of a collective, evolving infrastructure challenge—not as a final or closed solution—and we welcome technical feedback, corrections, and collaboration.

6. Overall Conclusion

The demand for modern, verification-ready LCIA methods such as TRACI 2.2 and EF 3.1 has outpaced the native support provided by the major LCI data sources most widely used in North America. This mismatch has created a structural gap between what program operators require and what datasets directly supply.

In this work, we set out to address that gap in the most conservative, transparent, and defensible way possible, with two primary objectives:

Enable TRACI 2.2 support for ecoinvent, and

Enable EF 3.1 support for USLCI, without introducing uncontrolled assumptions, forced matches, or opaque heuristics.

To do so, we grounded the implementation in:

- authoritative community-maintained mapping resources (OpenLCA, GLAD, EF reference packages),

- a hierarchical matching framework that prioritizes authority over automation, and

- a multi-layer validation program spanning structural coverage, process-level stability, and outlier analysis.

The validation results demonstrate that:

- TRACI 2.2 on ecoinvent behaves exactly as designed, with all non-eutrophication indicators preserved and eutrophication changes introduced only through the intended regionalized characterization.

- EF 3.1 on USLCI exhibits strong directional agreement with TRACI 2.2 at the process level, with no evidence of mapping-driven numerical instability.

- Observed differences between methods are consistent with legitimate methodological differences, not structural mapping defects.

At the same time, this work reinforces an important reality for the LCA community: elementary flow harmonization across independently developed datasets and LCIA methods is an inherently imperfect problem. No technical framework—no matter how rigorous—can fully eliminate semantic uncertainty, chemical representation differences, or model-level divergence between methods.

Our position is therefore deliberately balanced:

- These mapped implementations are fit for verification-driven use when native alternatives do not exist.

- They are not a substitute for native dataset–method integration by data providers themselves.

- And they should always be interpreted with full methodological transparency and contextual care.

Ultimately, this work is intended to move the industry one step closer to consistent, modern impact reporting across heterogeneous data ecosystems, while remaining honest about the limits of what mapping can achieve.

We hope it contributes constructively to the ongoing, community-wide effort to improve interoperability, reproducibility, and trust in LCA and EPD practice.

Appendix - Useful Flow Mapping References

OpenLCA LCIA Methods - A comprehensive, community-maintained package of life cycle impact assessment (LCIA) methods provided by the openLCA Nexus. This repository includes standardized implementations of methods such as TRACI, EF, ReCiPe, and others, along with their full characterization models and elementary flow definitions, and serves as a primary reference for LCIA method harmonization across datasets.

GLAD Elementary Flow Resources (Github) - The Global Life Cycle Assessment Data Access Network (GLAD) elementary flow resources provide publicly maintained reference flow lists, mapping files, and supporting metadata used to harmonize elementary flows across multiple LCA databases. These resources underpin many cross-database interoperability efforts and are widely used in flow-mapping research and practice.

GLAD Elementary Flow Paper - A peer-reviewed research publication describing the GLAD elementary flow harmonization framework, including the development of a global reference flow list, standardized identifiers, and cross-database mapping methodology. The paper documents the theoretical foundation and validation of the GLAD approach and serves as a key academic reference for elementary flow harmonization.

Federal LCA Commons Elementary Flow List (Github) - The Federal LCA Commons elementary flow list and supporting mapping files published by the U.S. government provide the authoritative set of USLCI elementary flow definitions and their official mappings to OpenLCA reference flows. These resources establish the canonical translation layer between USLCI and OpenLCA and are critical for consistent characterization across U.S. federal LCA datasets.

Ecoinvent–TRACI 2.2 Options (Notion Article) - An internal technical memo from SmartEPD documenting available strategies for enabling TRACI 2.2 impact assessment on top of ecoinvent inventories, including evaluation of flow-mapping requirements, characterization factor availability, and implementation tradeoffs.

EF 3.1 Reference Packages - The official European Commission reference packages for the Environmental Footprint (EF) 3.1 method, providing the authoritative set of characterization factors, reference flow definitions, normalization data, and supporting metadata required for EF 3.1-compliant impact assessment.

Share

Got a Product in Mind? Let's Model It Together.

Tell us what you're working on, and we'll show you how CarbonGraph can bring it to life with environmental insights.